GUERRIERI, CAVALLI E CENTAURI

GUERRIERI, CAVALLI E CENTAURI

Long shadows of lasting memories

It is difficult to establish if it was the destiny of an emotional wake, of a familiar story told by Staccioli himself, or that of the horses, to be entangled together in a common path.

“Straddling time” we create a stratification perhaps truly experienced: a little horse on wheels, a toy, that we see in the hand of the artist’s father pictured in a photo from 1917 when he was three years old. Or perhaps the long before Horse with wheels, a little toy in terracotta from the tenth century B.C..

The hooves will paw the ground, yet again, from that far off place to this present time. Only the neighing will fade away. Lasting memories. Here they are reappearing in dreams, going around on a carrousel, circling together with cherubs; they mix with the dust and sweat in Paolo Uccello’s Battles. Horses that Paolo Staccioli , in the eighties, made the protagonists of his visions, poetically break into his pictorial and sculptural world. “And if –as Cristina Acidini wrote on the occasion of the exhibition at the Museum of Sacred Art in San Casciano Val di Pesa ( Florence) in 2007- the horses drawn, incised, and molded transmit such a sense of vitality and uninhibited freedom that we can compare them to the animals depicted on the cave walls by the unknown artists of the Paleolithic age, also for them we can predict a constraint of a repetitive movement predisposed and controlled by an unknown authority when they are placed in a circle, running one behind the other in an improbable little carrousel in which gaiety is a thin veneer.”

For Paolo, the horse is a mythical, divine anima, molded by the goddess Athena, embedded in her memory, with liberty, lightness, and the irony has been recognized by the critics since the early days. (Nicola Micieli 1997, Tommaso Paloscia 1999, Antonio Paolucci e Ornella Casazza 2005, Claudio Paolini 2011).

The art of riding, that passes through Time, enters into his figurative repertoire, revealing itself to be rich in suggestions, masterfully articulated. Closed in his studio, “the ancient culture and tradition – as Antonio Natali said in the catalogue of Paolo Staccoli’s showin the town hall of Scandicci in 2017- continue to propose themselves as models, not as nostalgic sentiments, but rather in virtue of the conviction that the past, when it is lyrical and cultured, always remains an indispensable example for living, fully aware, in the times that have befallen us.”

In silence, the artist reflects, shaping far off memories of pleasures had through writings, in the halls of museums “rediscovered and recreated with freedom and condor; he shapes his identity and his game is played out in a contradiction between the need to be modern and ancient; a conservator of forms and iridescent surfaces” (Ornella Casazza 2001).

He retrieves avenues of tensions, suggests variants: ironic is his Eros who, like a winged baby, plays alone or with other divine children molded around the neck of a vase which he made in the 1990’s (that reminds us of vases made in ancient times at Canosa di Puglia) ( Maria Anna di Pede, 2009) in raised slip decorated faience, painted with oxides and salts under the glaze , and highlighted with gleaming reflections of sunset or lunar iridescence, favored by the fires complicity.

A cherub knows how to ride a horse, since April 2000, in the beautiful nature of the Poggio Valicaia park, above Scandicci, hugging the neck of a mighty bronze horse, two meters tall, green like Paolo Uccello’s terra-vert horses, that he securely guides to explore creation and the way of mankind.

With unpredictable novelty, skillful composition, expressive genius, Staccioli builds imaginary and visionary images of reality in his relationship with the landscape; a landscape that is always the same, charged with stories, set, moreover, into the stories of the horses, of light knights, floating in a void, of characters precariously balanced on genuine swings; shapes packed into the spaces, without a prospective or temporal hierarchy. Near and far, before and after lose their meaning.

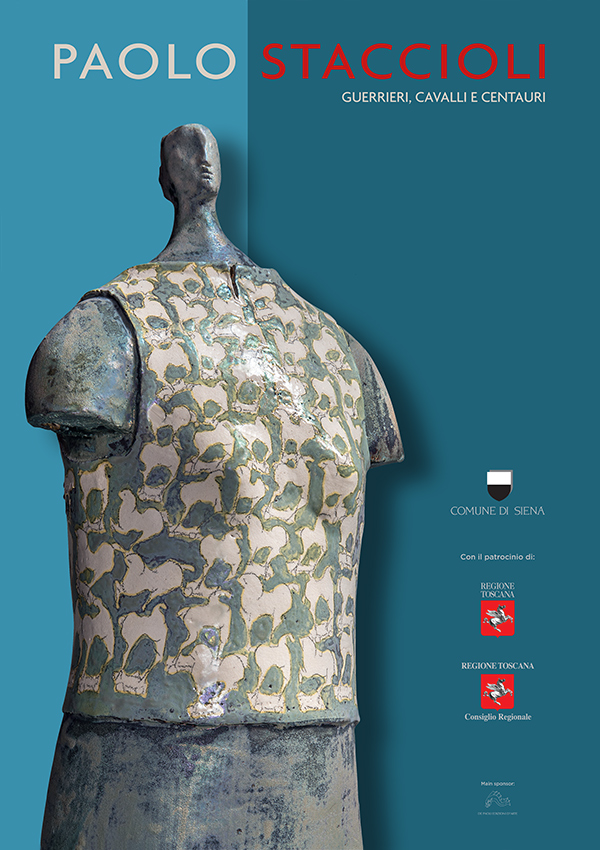

Spatialness, always understood by the little horses in relief, defines itself in the amour of his good and immobile warriors who, even though they may have a feeling of longing for a place where they have never been, will never return or depart to fight, even though they are armed with lances and shields.

Then there is nostalgia, the punishment for being far away. It is the loss not of a place where they would like to return to, but rather who we were in that place at that time and which we can never be again. But salvation for Paolo is the encouraging of a current of disquieting upheaval that brings us back to an emotional land that is unknown to us.

Groups of seven, eight, ten, one hundred appear, then, melancholy, united by a solid naturalness: numerous and silent warriors, enigmatic travelers who, even though they are ready for a return journey into memory, they do not leave; they are waiting perhaps for a group of “Traverlers with spheres” in coats and ties, gaudy, who hold a sphere in their hands or on their shoulders, ordinary Atlases who hold up the world.

Mythography of the present, these male and female figures distance themselves from reality, in a world that does not exist but is tangible in Staccioli’s mind when he reflects upon surreal and metaphysical memories.

Read even the other critical text by Antonio Natali about the Paolo Staccioli's exhibition "Guerrieri, cavalli e centauri".