Human Constructions

Human Constructions

The dream of a radio that thought it could think.

There was a precise moment in the thousands of years of Western culture, among the many that can be traced back, for a variety of reasons, to the varied origins of the numerous aspects that make up what we usually call “Modernity” (from Giotto to Duchamp via Piero, Titian, Velázquez and Picasso), when it wasn’t so much the object, the form or the language of art that underwent radical change or alteration, as its innermost soul. Right up until just before the Storming of the Bastille, in that bloody July of 1789, art and artists had been devoted to celebrating the highest ideals referable to a specific commission, embodied primarily by God, Royalty and Government. With the fall of the French Ancien Régime, a sort of new Sack of Rome or an early 9/11, art discovered new ideals and new themes to investigate; in a manner of speaking, it discovered its “dark side”. It was no longer a celebration of the high and immortal glory of kings, emperors, princes or popes, but of everything which had previously been rejected and rebuked: reality, even (and especially) in its lowest form. Art no longer aimed solely to embellish, imitate, create and recreate an ideal, but became a primary tool, to use the words of Michel Foucault, for “denuding, unmasking, denouncing, scraping, digging, violently reducing existence to its primary elements”. Which continues with: “There is no doubt that this vision of art progressed more evidently from the middle of the 19th century, when art (with Baudelaire, Flaubert and Manet) became a place of irruption of what was lower down, beneath everything, that has no entitlement or chance of expressing itself in a culture. […] Anti-Platonism: art as a place of irruption of elementary things, as the denuding of existence. Consequently, art has established a difficult relationship of reduction, rejection and aggression with culture, social acceptability, ideals and aesthetic standards. This is what made modern art, as of the 19th century, that incessant movement through which every rule established, deduced, induced and inflicted on the basis of each of its previous actions, was rebuked and rejected by the subsequent action. In every art form there is a sort of permanent cynicism with regard to every acquired art form: this is what we could call the anti-Aristotelism of modern art. Anti-Platonic and anti-Aristotelic modern art: denuding, reduction of existence to the elementary state; rejection, perpetual denial of every form already acquired. These two aspects convey to modern art a function which we could briefly define as anti-cultural. The conformism of culture has to be opposed by the courage of art in its barbaric truth. Modern art is cynicism in culture, the cynicism of culture turned against itself. And it is especially in art, although not exclusively, that, in the modern world, our world, the most intense forms of that desire to tell the truth that is not afraid to wound its interlocutors are found. Naturally there are still many aspects that have to be analysed, particularly that of the genesis of the question of art as cynicism in culture.”

Regardless of the important consequences, which later degenerated, induced by this cultural “revolution”, what we need to highlight here is the importance taken on by new and unprecedented issues in modern expressivity, such as ecology and the environment, which are fundamental in the work of Tironi and Yoshida covered by this essay.

This is not the place for an in-depth debate on such a long-standing yet so current subject, but it is important to draw attention to its fundamental role and basal nature, among the many complex themes that can be found in the genesis of the considerable expressivity of this young duo of sculptors.

The stylistic and poetic choices made by Tironi and Yoshida are only apparently simple, being traced back (without completely adhering) to a thread, initially Dada and then Nouveau Réalisme, which, in the wake of that as then unprecedented approach to the concept of “art”, particularly French art for the reasons mentioned earlier, had numerous, not always successful, epigones during the “short century”. With Tironi and Yoshida however, as often happens when foreign phenomena cross the boundaries of Italy, the French experience is enriched with new and unexpected aspects, breaking through into a visionary, ironic ideal situation, so full of Beauty and metaphysical values.

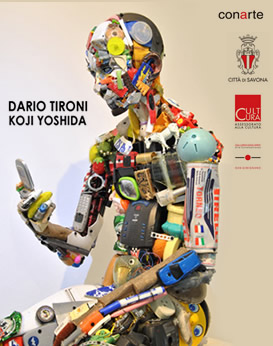

While the followers of Dada (and their new counterparts), descendants of Duchamp and the Noveaux Réalistes focused attention mainly on the mental project, on the event and on the action of the artist, as opposed to the work (a lesson gleaned later on, with regard to the reporting of environmental problems, from the “actions” of Joseph Beuys) in the case of these young sculptors from Lombardy, it is always the final work of art that is the unique result of a concept and of a project that are well-defined and anything but “Foucaultianly” cynical; a work which, not by chance, and despite being made with anomalous materials (electronic scrap, “pop” rejects, fragments of toys forgotten and unloved), encompasses all the characteristics of a classical sculpture, including that Beauty so deprecated in the modernity of horror and provocation at all costs. The Dada “action”, in the work of Tironi and Yoshida, is limited and restricted to an original, effective and elegantly provocative use of unusual and “poor” materials, to the sublimation and almost alchemical transformation of forgotten objects lacking in value (including, but obviously not only, aesthetic value) into “something” completely different, which is aesthetically and expressively valuable: into sculptures which, thanks to Beauty and harmony, restore lost dignity to forgotten, useless objects.

While in the Dadaist works or those of the Noveaux Réalistes the nature and origin of the object continue to be closely linked to themselves, to avoid detracting attention from the action, in the works of Tironi and Yoshida, camouflage is absolute and only a very watchful and far from fleeting eye can see their truthful nature, simultaneously highlighting the poetic ideology of the environmental claim. It is a sublime and highly refined operation of pure, timeless surrealism, closer, and not accidentally, to the inventions of an Arcimboldo rather than to those, characterised by plenty of very refined but more provocatively extreme conceptualism, of Duchamp, Man Ray, Magritte, Dalì, Picasso, Miró or Chevalier. French surrealism contains the invention of what would otherwise be impossible in reality; in the works of Tironi and Yoshida there is the recreation of all things visible, of what we know and what is real, taken to its highest and most sublime level, as in the case of quotations from immortal works of Western art. Our duo has performed an operation which, paradoxically and surprisingly (due to Japanese reference traceable immediately to the origins of Koji Yoshida), can be referred more to the work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Japanese master xylographer of the 19th century, for the fine, fresh and pungent irony, the clarity of the prototype, vital buzz and intelligent parody.

It is through these elements that the sculptures of Tironi and Yoshida charm, seduce, intrigue and entertain, restoring art’s fundamental prerogative to induce reflection, to question and consequently teach, on a theme which is currently of such urgency. To restate the subliming and transfiguring power of art, but also the ability of human genius to create in the wake of every form of destruction.

Galleria Gagliardi - 2011: solo exhibition "Human Constructions" by Dario Tironi & Koji Yoshida curated by Alberto Agazzani

1. See Foucault, Michel, Le Courage de la vérité. Le gouvernement de soi et des autres II, Cours au Collège de France, 1984. Paris, Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Gallimard, Éditions du Seuil, coll. « Hautes Etudes », 2009, 368 p.

2. Ibid.