GUERRIERI, CAVALLI E CENTAURI

GUERRIERI, CAVALLI E CENTAURI

Warriors, Horses and Centaurs

Paolo Staccioli and the modernity of Myth

There is a quality that runs – like an uninterrupted line – through the history of our territory: austerity – formal and intellectual - always, in fact, imprints itself on the culture of the people living in Tuscany. It has been going on since ancient times and it touches our present time as well, despite that the current tendencies ( which according to the usual opinion derives from the west, coming from across the ocean) are bearers of images and messages capable of standardizing and dulling minds and hearts, even the most diverse.

It is quite needless to talk about the Etruscans, because the severity of their artifacts and their art is clearly evident and doesn’t need commenting. Anyone who knows anything about the Tuscan Romanesque and Gothic knows well that they distinguish themselves precisely for their sobriety ( here in the Siena territory, prime examples of this are the outlying country Pieve churches and, in the city, the marble of the Duomo just slightly refined by the amiability that has always contributed to the senese style). But, also Humanism and the Renaissance - which, particularly in Tuscany, reach an absolute high – virtually feed upon the same rigorous austerity, which moreover in these two periods, become even an emblem. (Siena, without deviating from its course, still shows its traits of domestic affability and at the same time nevertheless nobility). We won’t speak about the 1600 and 1700’s because here they abstained from Baroque exuberances and Rococo caprices. Nor could the “macchia” painting have begun elsewhere in the 1800’s with its frugal vision of nature often painted on scant little panels. And final, there are the authors of the 1900’s who actually return to the grave and massive interpretations of reality of the early 1400’s. We can remember the study by the Tuscans – Rosai in the lead- of the Brancaccio Chapel, conducted in the same manner as the great artists of the early 1500’s – from Michelangelo to the young Raphael – who went to the Carmine ( church) to copy the stories frescoed by Masaccio.

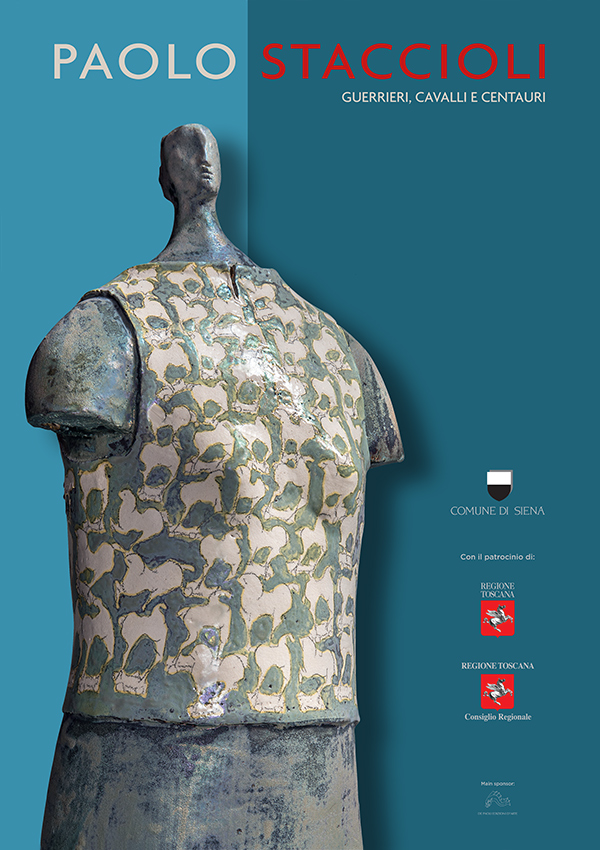

So, Paolo Staccioli’s sculptures fit well into the itinerary we have just laid out. His figures –real yet abstract, turned and levitated, austere even when they are refined with elegant and colored decorations and even some golden hues - are marked by a severe character that from a primordial beginning crossed , under the surface, the culture of our territory.

His warriors, of solid construction, compact as if their amour was an integral part of their bodies, making them invulnerable, are of the same kind as the Warrior of Capestrano, but, if possible, even more primitive. The amour is without hinges, making it seem like their limbs could sprout from it like from the shell of a Bezzuga. In their presence, I have cultivated the fantasy of seeing tens of them regimented like the Chinese terracotta army. And, I have imagined their formation, full of identical figures positioned in a long silent parade, not symbolizing the defense of the emperor, but rather evoking a humanity that this time lines up to protect itself against the homogenizing effect imposed by the informatics regime, the latest despot. A humanity, strengthened by a solid historic conscience, does not fear the new, but rather the invasive and overbearing violence by something new that leaves scorched earth behind it.

I can imagine, in this senese context, Staccioli’s warriors standing tall under the arches of the Salt Warehouse, in the rooms that open one on to each other in a sequence or in the passageways protected by railings. Warriors, that after the rite of the investiture of arms, prepare (just like gladiators waiting to enter the arena) to align themselves in a geometric formation on the brick paved slope of the theater shaped square Piazza del Campo.

In Staccioli’s creations, ancient culture and tradition continue to propose themselves as models, not as nostalgic sentiments, but rather in virtue of the conviction that the past, when it is lyrical and cultured, always remains an indispensable example for living, fully aware, in the times that have befallen us. Watchful like sentinels, the “warriors” ( I will continue now to call them like this) molded by him, are not opposed to the new times; they nevertheless monitor that the noble past is not forgotten or even mocked. Their militance will be useful to the younger generations for whom the memory of the ancient past should ring as an amiable, not tedious, lesson, unlike how a no longer passionate scholastic training makes them feel.

And yet, again, the exhibition location invites us to direct our reasoning toward the past and the present in a dialogue between a work from our time and one painted instead between the 1300 and 1400’s, specifically by a senese artisan. In 2017, in the halls of Palazzo Strozzi, on occasion of the Bill Viola show, a rapid sequence of small videos was shown, simulating the compartments of a predella where stories were played out of women alone, closed in the humble and unadorned rooms, each one absorbed in a domestic chore, like nuns at work in the cells of a nunnery. That sober sized series (entitled Catherine’s Room, 2001) modeled on a panel by Andrea di Bartolo, pictured, under a portico of fine arches – in precisely the style of a predella – scenes from the life of Saint Catherine from Siena, portrayed in a prayerful disposition aware of a languid mysticism. There is a close relationship that in Palazzo Strozzi was reiterated with the comparison of the two works presented one in front of the other , without hierarchy.

But where modernity barricades itself in intransigence and surrounds itself with bastions, under the grim protection of an absolute lord, lofty tradition will have the right to take the fortress by force. And, in fact, this is the metaphor that spontaneously comes to the surface, when attention is shifted away from the hieratic warriors and directed toward the horses on wheels: an icon halfway between the synthetic abstraction of Etruscan austerity and the weighty elegance of Marino’s figures. The image of a horse on wheels will also evoke the stratagem that Ulysses devised to outwit the Trojan resistance. One could say, moreover, that from this astute expedient a symbol indeed could arise. And in the wake of this mystical dream, we can imagine a maniple of that army of military men, solid and severe, that infiltrate the fortress, populate by digital creatures, hiding in the belly of a monumental simulacrum of a horse whose wheels permitted it to cross the threshold of the stronghold, maybe even pushed in – like in the Homeric epic – by those who would then suffer the consequences. Revenge of ancient culture over arrogance 2.0.

Every actor on Paolo’s theater stage is a silent creature, engrossed in thoughts impossible to communicate, as if they were a Kouros or a Kore, when a hint of breast is slightly visible under the patterns of the ceramics, soberly elegant, place to dress the torso. A solitary creature , alone even when it is not, even when it gets on a cart with other figures or with others still, rides – on a carousel in miniature – one of the little horses rearing up on its hind legs that pursues, in a circle, the others without any hopes of ever catching up to them .

These are men and women of fables who are sitting on a world extraneous to them, with their backs turned to one another, disinterested in one another, ready now to leave on a journey, that we can predict will be brief by the their tiny suitcases.

There are mythical creatures, at times, of which the recent Centaur naturally becomes an emblem; he too, however, is fixed in a placid silence. In spite of his nature, half beastly, he presents himself as mild and even docile. He doesn’t have with him either a bow and arrows or much less a club. His arms are abandoned by the sides of his human torso and he holds in his left hand (low down though) a shield, that is more evocative of a defense rather than an aggression, as opposed to what one would expect from a centaur. We can read it in terms of an allegory: an allegory with a strong nature, but peaceful and good. And, anyone who knows the artisan knows what I am talking about.