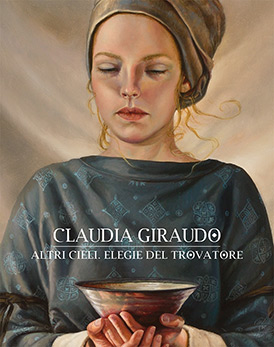

Altri Cieli. Elegie del Trovatore

Altri Cieli. Elegie del Trovatore

An imagined world, dominated by a dreamlike atmosphere, is a world where anything can happen. It is a world where each detail is processed and becomes allegory, since things cannot escape epistrophè, the return syndrome, always striving to join their respective archetypes. It is a world illuminated by the reflections of the mind, in a game of concentric drawings in which the horizons of symbology, and consequently of life, are discovered.

Claudia Giraudo walks us through this world with the works on display at the exhibition entitled Altri Cieli. Elegie del Trovatore, which belong to some of the most important cycles of the production of this artist from Turin, linked together by the fil rouge of poetry. Whether it is intended as a symbolic tribute to the production and creation of the poet, custodian of the Mystery, or materialises in the world of the circus and, in particular, in the figure of the tightrope walker, that which ties together all of Giraudo’s works is this underlying soul that aims to poetise life as a form of coincidence between the imaginary world and the existential one, between desire and the object of that desire, following all of its visionary aspects.

Man, whether poet, tightrope walker or artist, is always intended as an intermediary or connection between earth and sky, capable of opening that which is near and to reveal that which is far away. Poetry thus becomes a spiritual language that shares with artistic creation the Freudian status of a form of sublimation and consequently of guidance during man’s journey through life.

That is how and why today, in a consistent itinerary that does not give in to the flattery of the “easy” image, the latest work dedicated to poets is being added. Presented for the first time at this exhibition in Rivoli, the work is inspired by a film entitled “The Colour of Pomegranates”, by Sergej Paradjanov. This film, characterised by an extreme evocative and symbolic power, and dedicated to one of the most well-known figures of Armenian literature, the troubadour Sayat-Nova (1712-1795) is however just a pretext that becomes a stimulus to reflect on the world of poets and on what they represent in the universe of Claudia Giraudo. Hence, we find ourselves looking at works that explore the essence of lyrical creation and call to mind the related images and symbols (Io cerco un Tesoro [I’m Looking for a Treasure], L'Arte del Trovatore [The Art of the Troubadour] and Pour Vous [For You]), and other works where poetry is broken down and analysed in its male and female principles (Il custode del Mistero [The guardian of the Mistery] and Il canto sussurrato [The song whispered]), figures that express their essence even through their daimon. The figure of the daimon is a recurring one in Giraudo’s works, the “key” to understanding the “vocational” calling of each one of us in this life. We find this figure in Plato, in the Myth of Er, at the end of the Republic and again in Plotinus: each human being is the bearer of a unique essence that asks to be experienced, a sort of fate that is also a calling, which the soul consciously and unavoidably chooses, of which the daimon is responsible for reminding us.

Giraudo’s reflection goes beyond, using these symbols in order to follow that active imagination that allows one to focalise life from points of view which are not ours, to think and feel starting from different perspectives. And so the Skies above us are not only those of the Troubadour, but instead are many and full of allusions and references; they are Other Skies, under which different figures move, tied together by threads that mark their connections, or on balance despite impossible contrasts between lightweight and heavyweight, or again belonging to a circus-like world meant as a metaphor for life’s illusion: figures with basic gestures permeated by a deep symbolic strength, “set on a stage” in a suspended time, which are nothing but delicate elegies, fascinating paradigms of the condition of man and of Art. So, scenarios open up right in front of us linked to the circus world, next to surreal animals and still life, inanimate yet alive due to their being inhabited by vital presences (Cruditè; Fantarcheologia II). All subjects are like figures of an alternative mythology limited to a few gestures, consequently emphasised and made into icons, hanging against backgrounds that look like abstractions, with no context whatsoever. The circus people are portrayed during their break, outside the setting, so as to underscore even more the metaphor of man’s condition. There are acrobats, dancers and tightrope walkers, all in their stage costumes and props, hidden behind their colourful make-up and extravagant outfits, in the echo of the perceived sounds of a show that has just ended or is about to start, in the magic of their brief performance and of their nomadic lives. The ephemeral and the tangible elements are inevitable constants which continuously oppose one another, and in the mediation between these two conditions, suspended in this harmony made of contrasts, the tightrope walker finds his role next to the poet, the artist and the daimon which, present in all cycles as the figures’ companion and as a guide that possesses similarities with the myth that lives within us, also becomes a metaphor of the human condition, in its search for a constant point of balance. When we look closer at the works of Claudia Giraudo, we notice that, contrary to their appearance, they are actually very modern: far removed from any apparent hyperrealistic intention, they show a surprising rethinking of painting, a reconfirmation of the nature of painting that surprises us since, rather than leading to a vision of the world or of the being, it seems to unveil a knowledge of the images that goes deep down and through them. The images that we observe are narrations, albeit in a very rarefied sense of the term. These works represent the closest thing to the thought of Jean Baudrillard, who prefigured the death of the work’s aura, and to the concept of meta-narration of Jean-Francois Lyotard. They are a sort of Mannerist variant of the principle of montage, a version of post-modernism where we are confronted with the entire baggage of the artistic tradition, from Vermeer to Magritte, with no diachronic or hierarchical distinction whatsoever. These are works that position themselves between appropriation, anachronism and symbolism, in an extremely particular and unique overcoming, which lives in the constant memory of one’s identity. It is a very complex processing, one that cannot be immediately interpreted, which conceptually turns Giraudo into a real Mannerist who is also a post-modernist. All of the above is joined by an exceptional technical quality and a strong richness in contents, which overlap each other to then dig down inside of us, as poems full of deep and composite layers, which nourish us every day through growing assimilation.

So, a quote from André Breton comes to mind: “un cattivo scrittore è come una macchia d'acqua sulla carta, si allarga rapidamente ma ben presto evapora. Un buon scrittore è come una goccia d'olio: quando cade fa una macchia piccola, ma con il passare del tempo si allarga su tutto il foglio fino a riempirlo”. (1*) A bad writer is like a water stain on a piece of paper: it quickly expands but soon evaporates. A good writer is like a drop of oil: when it falls it makes a small spot, but over time it spreads out over the entire page until it fills it]. Perhaps it is precisely that discrimen that makes “real” poetry (the true artistic creation) that miracle capable of changing one’s view of the world.

Galleria Gagliardi - 2015: solo exhibition by Claudia Giraudo "ALTRI CIELI. ELEGIE DEL TROVATORE"; critical text by Alessandra Frosini

1* A. Jodorowsky, La Danza della realtà, Milano, 2001, page 153