ISAO SUGIYAMA

ISAO SUGIYAMA

THE IDEA OF THE MATTER

The great pathway has no doors,

Thousands of roads lead off it.

When you cross that door without a door,

You walk freely between the sky and the earth.

Mumon

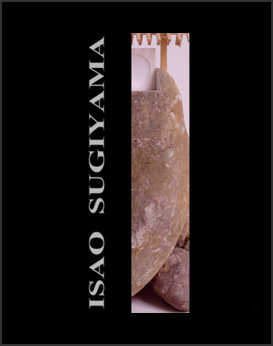

1983, the year in which Sugiyama came to Italy on his first trip to the West, which should have taken him to the United States, was both a great discovery and an absolute "disaster".Sugiyama had just finished years of study in Japan, during which he had achieved an in-depth level of knowledge of sculpting techniques, and dedicated his talent to figurative works with an academic imprint. The sudden heavy confrontation with originals from the past - from the marbles of ancient Greece onwards - aroused a sense of inadequacy and uselessness in the artist which brought him to consider the possibility of changing his job. The subsequent meeting with contemporary art allowed him greater creative freedom, away from the restrictions of the past, helping him to regain hope and to reconsider the very meaning of the word "art", which, from that moment on, was no longer an abstract entity stipulated by a maestro, but a deeply personal and vibrant element in resonance with the "soul" of the creator.The artist dedicated the years that followed to a study of himself, to gaining the maximum from a cultural heritage which wasn't limited to his artistic studies, but dated back to his childhood in fifties Japan, in economic poverty but with a richness of tradition and values which still exists in Japan today. In Europe the artist found a reason to free himself from many strictly formal and constrictive rules which had distanced him from some of his passions and innate abilities. Sugiyama's childhood passion for modelling and manual craft, were put to use in his work as an adult, developing and emerging in a new more refined game, executed with the same self-congratulatory carefree air. The fact that he settled in Carrara, where he attended the Academy in the Eighties, made marble the star of his sculptures. Sugiyama likes to use the materials he finds locally; the various types of marble lend themselves to various uses and formal alternatives. Needing to cope with the Italian situation on an everyday basis the artist discovered that he was full of oriental sensitivity. Images of the scintoist cult, the oldest in Japan, made inroads into his memory and were expressed in sculpture. Sugiyama says that it is a very similar religion: there are about 8.000.000 Gods which are worshipped and they correspond to natural elements like the sun, trees, the wind… in a direct relationship with nature which is not competitive but trustful, which the artist fails to find in the West. His love and respect for natural elements are expressed in the way he handles materials: marble and wood - those used most frequently - are united so that they d not become a completely human work, but retain their original form and texture. For this reason the Carrara marble "potatoes" - large tubers of stone with a dark, uneven surface and a candid inner - are perfect. The artist loves to use them as they are, or cut up to reveal an unexpected whiteness which contrasts with the external rustiness. Often the stone is cut so that the base remains one with the elements that form the holy architectures, the so-called sanctuaries that have been Sugiyama's topic of research for about ten years. The key to link nature and culture, childhood games and professional sculpting, materials and ideas, past and present, lies in the theme of the sanctuaries - two hundred sculptures that the artist has conceived and patiently built day by day. The ten typologies that the artist individuates within the general theme refer mainly to the structure and the combination of elements: in some the mass is full and imposing, in other the surface is covered with hollows; there are decorative details here and there, such as "drops of sunshine" (simple carved or relief motifs) discreetly disseminated. The marked contrast between masses left in their original state and the highly polished, white surfaces, sometimes so fine that they become transparent, is amazing. These however are contrasts which exist in nature, which are able to emerge thanks to human intervention. When, as in “Sanctuary 135” (1997) a perfectly geometrical, two-tone temple rises precariously from three “potatoes” of rough marble, the artist draws purity from the stone's natural resources, impersonated by the divinity to whom the temple is dedicated. To ensure that the god fills his sanctuary, the scintoist priest cleans it perfectly. The space must be empty and immaculate. The faithful may not enter, remaining outside to pray; white fabric hides the threshold so that only glimpses of the interior can be seen. Thanks to the fine surfaces of marble, in Sugiyama's sanctuaries' stone curtains are sometimes embellished with perforations down the side, adding a feeling of lightness to the transparency allowing air - or the soul - to flow through. The long staircases that often - as in the sculpted complex “A holy place” (1993) - lead to the door (mon) of the temple, are a route to purification; when they are interrupted by a chasm, an empty space that seems to block the way, it is the soul - the imagination - that overcomes natural limits as it frees itself. Wood is the material that most frequently accompanies marble in this dialogue between soul and matter. In works like “Sanctuary 154” (1998) the pine wood trusses of the temple are bound directly to the marble using a Japanese interlocking technique which suggests continuity and is the result of great technical expertise. The geometrical precision of the small beams contrasts with the irregular, asymmetrical surfaces of the base, according to a typically oriental aesthetic need; the whiteness of the pine, which hints at purity, replaces the more precious white wood native to Japan. Sugiyama freely expresses his passion for the internal bone structure of things, like when, as a child, he was more interested in the nude framework of the models than the finished article. The immense patience and great concentration needed in many technically complex situations enable him to get away from everyday problems and float away into a universe all of his own, suspended between imagination and materiality. The sanctuaries of Sugiyama, constructions which combine polished geometry and rough natural surfaces, calculation and casualness, mathematical proportions and free asymmetrical shapes, are like miniature worlds that reproduce deep truths on a small scale. In the unequal relationship between man and nature, the artist modestly bows down before the infinite flow of the universe. Time, which corrodes and crumbles wood, just like marble, in its cyclic progress, acts deeply upon things, reminding man that his work is just a drop of water in the sea of life.

Monica Dematté, born in 1962 in Trento, Italy, graduated in visual arts at DAMS. PhD. In Indian and Far-Eastern Art History at Genua University. She studied Chinese at Sun Yat-Sen University in uangzhou, and Chinese History of art at the Academy of Fine Arts of Guangzhou. She worked as a curator at the Singapore Art Museum (Singapore), specializing in Chinese Modern Art. She holds a lecturer position at Venice, Ca’ Foscari, as well as at Bologna University. Independent writer and curator, her essays have been published on art magazines both in Italy and in China.

Galleria Gagliardi - 2001: solo exhibition "Isao Sugiyama" curated by Monica Demattè