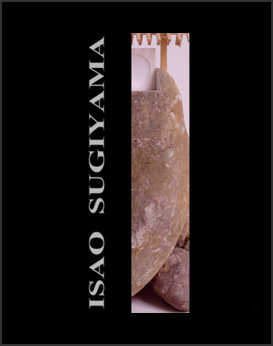

ISAO SUGIYAMA

ISAO SUGIYAMA

EPHEMERA THINGS ARE ETERNALOf

all the symbols of eternity and security, that which appears most frequently is the Home. The Home is the individual version of the World, in other words, the universal home of all men. This use of symbols embraces all cultures and there is no religion which hasn't adopted it. In Jung's terms, we might say that we found ourselves before an archetype, something that doesn't change with time, which isn't affected by changes in taste. From Hindus to Christians, the problem involves possession, construction, finding shelter, a place to call one's own: an elementary yet eternal need. “Going home” is synonymous with happiness and safety, and "mum and dad's house" or "The House of God" are always ready to welcome prodigal sons who've left the nest in search of knowledge. Knowledge opens the way to thousands of roads, all of which are equally probable, but in choosing means finding the way back. This is not easy. Our existence is fragile; we live temporary situations as long-term arrangements. Man easily makes mistakes, often blinded by a fictitious, false and persuasive "reality", like the sirens of Ulysses.Isao Sugiyama faces all of these themes with exemplary clarity. His Japanese culture leads him to combine the complexity of thought with simplicity of shape which is surprising. The symbol of the Home is always there, in its holy form, that of "sanctuary", the home of the saints. This is strength, basic construction, but within this there is a non-apparent, but substantial fragility. It's almost as though the artist is hiding a crisis or a doubt inside his elaborate sculptures. Something similar happens inside the great cathedrals of the western world, at least according to the theory of the alchemist Fulcanelli. A magical point that when touched brings down the immense stones, windows and spires that challenged eternity. The artist perfectly combines extremes which are unlikely to be compatible: heat, cold, marble and wood, the transitory and the lasting, full and empty. The extremely fascinating side of his work lies in the sense of creating a link between opposing elements. Between inside and outside, for example, and the home is perfect for this, as it protects from things which are outside and, at the same time, creates a relationship between Man and nature. And this intuition is fundamental. Sugiyama considers the home as a diaphragm, in other words the work and fatigue of building something from nothing, of constructing and creating a human space subtracted with difficulty from the infinite outside space. And this synthesis is the work, work which is necessary to build but which is also necessary to create his sculptures which are always on the limit of the miraculous. His choice is spiritual. The act of building brings one nearer to God and to those saints who provide a link between visible and invisible. Sugiyama knows that man cannot give more than a certain amount, he knows about the immense work of man that God interrupted: the Tower of Babel. Man has to build his own house but he mustn't approach the Spirit through an act of arrogance. Man is ephemera, as we see in the sculptures of the Japanese artist, but he searches for eternity because this is the only way in which he can move forward, building himself a future, trying to impose his face over that of the Creator. The same Masonic, and therefore lay tradition, has left this message. There is more spirituality in building a house than in all the prophecies of Isaiah or Celestino. Sugiyama cleanses the soul of the man who architects his life, his family and his cosmos. The life of man is suspended on a narrow, dangerous bridge. But it is here that we have to live. And it is here that our time makes sense. The same knowledge and constructive patience becomes part of the work. His spiritual message crosses the barriers of time and work, this fragment of eternity that the artist transforms into the work. Every sculpture, every fine interlock, every subtle passage between materials, every particular joint, requires hours of fatigue and attention. Because the sense lies in instilling into every work a sense of something which is not banal, far removed from every mechanical procedure which would blacken it. The value of the “Great Work” has to be communicated in an alchemic sense. East and West touch in the delicate balance of knowledge. The work, the construction, the small yet immense architecture brings sense to the winding processes of knowledge. The meticulous attention to detail is not a stylistic affectation, but a poetic choice. The great work, the great care are all part of what the artist wishes to communicate, part of the meaning of the work. Even the time-work variable reconsiders the relationship between the artist with art and stands back from the poetics of things which are ready made, and is now approaching it centenary celebration. There is a return to considering the work as something philosophical, not a simple means of attracting money, but also authentic knowledge and a need for communication between the artist and the public. For this reason the spiritual symbol of the home, its solidity and even its temporary nature, confirm that “Ephemera things are eternal”. The words of Jorge Louis Borges come to mind - “We have to build on sand as though it were rock”. This is man's fatigue, building and combining different materials, searching for the impossible and finding it, perhaps in a sculpture, in the art of Isao Sugiyama.

Galleria Gagliardi - 2001: solo exhibition "Isao Sugiyama", curated by Valerio Dehò

Valerio Dehò has studied Aesthetics with Prof. Luciano Anceschi and Semiotics with Umberto Eco in Bologna. He graduated in Language Philosophy 1979. He now teaches Art Education and Pedagogy at the Ravenna Academy of Fine Art. He worked on the “Novecento” Project for the Borough of Reggio Emila from 1997 to 2000. He is currently employed as curator at the Kunsthaus in Merano (BZ). He directs the “Click Art Museum”, an on-line project linked up to databases on art i Europe. Since 1980 he has handled 106 contemporary art exhibitions in Italy and abroad and published 21 editorial monographs. He works for the art magazine “Juliet” and has written for the main Italian art magazines.