2021 - Galleria Gagliardi, Firenze, Palazzo Vecchio - Sala D'arme

IN THE ANCIENT BELLY OF THE PALACE

IN THE ANCIENT BELLY OF THE PALACE

War Exercises and Children’s Games

Exhibition and text by Antonio Natali

In the Salt Warehouses’ sever halls with walls and vaults completely in terracotta, positioned two stories below Siena’s Town Hall, Paolo Staccioli, in 2019, deployed his ancient warriors – infantry and knights – as if they were companies of men ready for a confrontation that would at any moment explode in the Piazza del Campo square, before the very eyes of curious folks looking out from the windows and balconies that face that metaphysical amphitheater.

Today that arrangement and expectation are recreated in the spacious and equally austere Armory of the Old Palace, in the ancient bowels of that building where the city’s government has always resided.

And so again, Staccioli’s warriors appear under the vaults, this time tall and wide, of this singular location. These warriors, after the ritual of the investiture of arms, ready themselves (like gladiators waiting to enter the arena) in a geometric formation that unfolds under the watchful eyes of the Lords on the steps of the Loggia of the Lanzi. It would be a lyrical suggestion, in today’s time (that is a golden time for installations), to have a bird’s eye view of this legion of silent and immobile soldiers, arranged in rigorous symmetry in front of the Old Palace.

These warriors, of solid constitution, compact as if the armor were made flesh on their bodies rendering them invulnerable, are of the same lineage as the Capestrano Armiger; but they are – if possible – even more primitive than he is. The armor has no joints; it is almost as if limbs could spring forth from it like from the shell of tortoise. At the sight of them, I have often nurtured the fantasy to see dozens of them, regimented like the Chinese terracotta Army. And I imagined their formation, packed with identical figures, arranged in a long silent parade, not symbolizing (as in the Orient) the courageous defense of the emperor even beyond death, but rather evoking humanity that takes sides to protect itself– this time – against a standardization force upon it by a computer technology regime, the latest despot. It’s humanity, reinforced by a solid historic conscience, that isn’t afraid of new things, but rather of the invasive and overbearing violence of those new things that leave scorched earth behind it.

In Staccioli’s creations, the ancient and the traditional continue to propose themselves as models, not as nostalgic sentiments but rather in virtue of the conviction that the past, when it is lyrical and educated, is always exemplary. It’s indispensable to knowingly live the season that is ours. Watchful like sentinels, the warriors (at this point I will continue to call them as such) that he has molded don’t reject new eras; they are watchful though that past nobleness isn’t forgotten let alone mocked. Their militancy will be useful to the younger generations for whom the memory of ancient things must become an amiable and not tedious lesson, as instead an impassionate scholastic formation makes it seem.

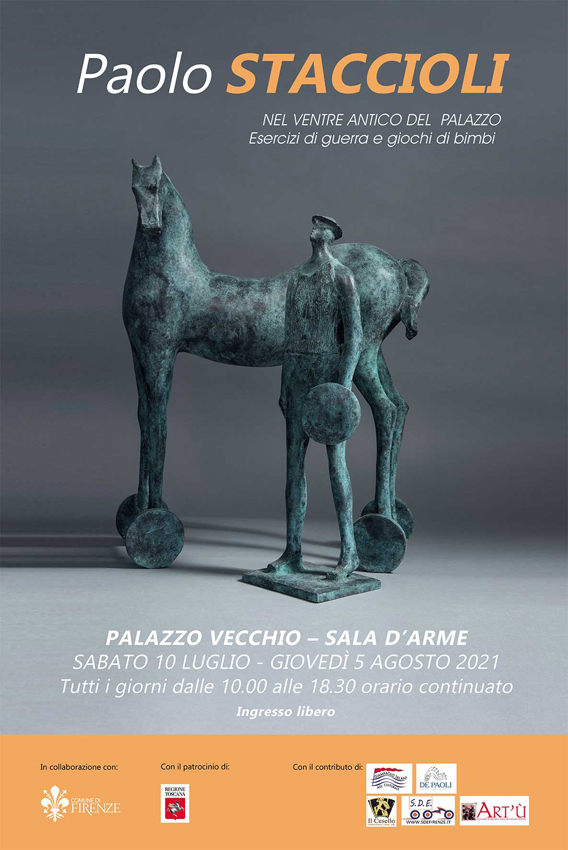

And yet again – now like two years ago in Siena – the exhibition location invites one to focus their reasoning on the past and the present; on the past of a building that represents the noblest medieval civilization and on the present of current creations, that don’t forget ancient culture. Ancient and modern together, equal in dignity, without supremacy. Yet when modernity entrenches itself in intransience and encircles itself with bastions, with the grim protection of its absolute dominance, stately tradition will have the right to conquer la fortress. And this indeed is a metaphor that spontaneously rises to the surface when one looks away from the imposing warriors and dedicates oneself to the horse on wheels: an icon between the synthetic abstraction of Etruscan austerity and the elegant severity of Marino’s figures.

The image of a horse on wheels evokes, in fact, the trick constructed by Ulysses to conquer the Trojan resistance. One would indeed say that the astute ploy could be likened to a symbol. And in the wake of this mythical dream, one can imagine a troop of that army of soldiers, solid and severe, that sneaks into the fortified citadel populated by digital creatures, hiding in the belly of the monumental statue of a horse, whose wheels allowed them to cross the threshold of the citadel; perhaps even pushed in – like in Homer’s tale – by those who would then suffer the consequences. Revenge of the ancient on the arrogance 2.0.

At the Old Palace, however, compared to the Town Hall of Siena, there won’t only be evocations of war exercises and preparations for armed conflict. In the armory, Staccioli’s warriors – realistic figures yet abstract, turned and levigated, austere even when the elegant decorations, colorations and golden reflections refine them – seem to return to a primordial state of their own invention, regaining a significance that perhaps was always implied by their very likeness.

From the beginning of this journey, one could ask oneself if in fact under their tough skins there doesn’t exist the spirit of a saga, of a legend that is very much like a fairy tale and even a game.

One can find a sign of this looking at the figure of the centaur, who, despite his half beast nature, is mild and even meek. He doesn’t have either a bow and arrows or much less a club. His arms are abandoned along the sides of his human torso and in his left hand he has a shield (but held low), which evokes more an idea of defense in a jousting match than an assault, which is quite the opposite of what one would expect from a centaur. So, one is lead to read it as an allegory. The allegory is of a strong but peace-loving and good character.

And following the exhibition itinerary, that initial question seems to reconfirm in the presence of a small bronze cart with three upright figures, as if they were part of a military parade organized as usual for a national holiday. A celebration that immediately afterwards assumes even more frivolity because of the Fellini like image of an oxidized iron rocker on which two adult characters in shiny bronze swing back and forth. And in shiny bronze is the female figure, lanky and imposing, that, seated on a high stool, dangles her legs and keeps an eye on a confused array of colored ceramic spheres, left scattered there once the game was over.

Yet again a game, an activity dedicated to recreation, to the absence of worries, to amusement and so it’s relevant to all the ages of man. Certainly though, it’s the prince of childhood, a season in which the desire to enjoy ones own present in the serenity of loving relationships is very much alive. The game thus becomes evocative of everything that favors agreement and harmony and opposes the evils of war - which can be allowed only when it is nothing but a game. So, in the armory of the Old Palace, Staccioli’s journey closes with a scene, placed to counterbalance his debut that is studded with armed knights and warriors. One of these, in bronze, with his bust finely armored, rises up in the middle of a group of white ceramic children each one with an iconographic attribute that identifies his age precisely; first a ball, then a horse on wheels, then a school satchel like we once used. Childhood besieges the warrior who moreover has tamed himself. He towers over all of them in height but his role has been converted in these peaceful days. The circle is complete. Supporting utopia.

Antonio Natali, 2021